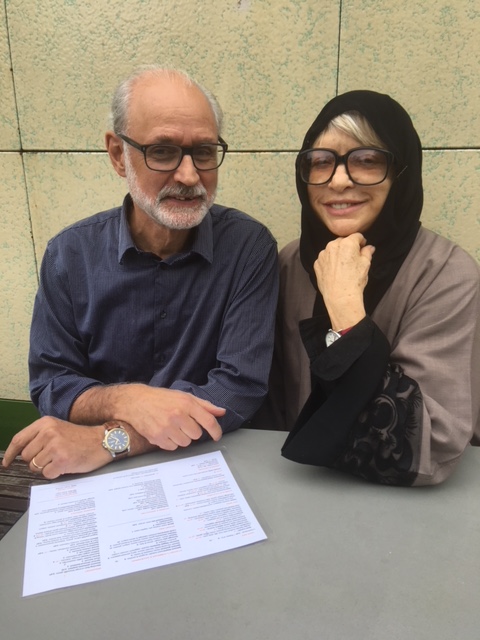

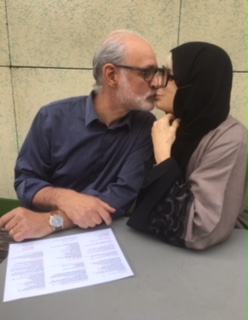

In Boston, when a woman in an Abaya is seen on the street, in a shop, at a restaurant with a man let’s assume everyone figures he is related to her and that the man is Muslim. And if he is Muslim, he is the person who has requested his wife, daughter, sister cover her body in public. Of course, since I am experiencing an artistic journey of how the abaya re-mythologizes me and those around me, this is not the case. I have been seen in public in abaya with my husband who is Jewish and who is most often but not always a willing participant in my choice of garment. When I asked how he feels about it all: “I just don’t want people to look at me and think I am oppressing my wife.”

In Boston, when a woman in an Abaya is seen on the street, in a shop, at a restaurant with a man let’s assume everyone figures he is related to her and that the man is Muslim. And if he is Muslim, he is the person who has requested his wife, daughter, sister cover her body in public. Of course, since I am experiencing an artistic journey of how the abaya re-mythologizes me and those around me, this is not the case. I have been seen in public in abaya with my husband who is Jewish and who is most often but not always a willing participant in my choice of garment. When I asked how he feels about it all: “I just don’t want people to look at me and think I am oppressing my wife.”

The rationale for wearing an abaya is attributed to the Quranic quote, “O Prophet, tell your wives and daughters, and the believing women, to cover themselves with a loose garment. They will thus be recognized and no harm will come to them.”

Wafaa, who gave me the abaya I wear, told me that the quote has been grossly misinterpreted because it only means that a woman needs to be modest. In some Middle Eastern countries, in the 80s, religious fanatics jumped on the words as rational to impose oppressive dress code that stunted female freedom, expression and presence. Fathers, brothers and uncles imposed the restriction on female in their families, even if they did not agree because the men had no choice but to fall in line with political, religious and social pressures. Females had absolutely not choice. In fact, Wafaa explained, even if a woman was living outside Saudi Arabia (for studies or work) if her father, uncle or brother told her she had to wear the abaya, she had to wear it.

But, she added, the rules in Saudi Arabia changed this year when the Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman said the decision is “entirely left for women to decide what type of decent and respectful attire she chooses to wear.”

That doesn’t mean women have tossed their abaya or the family men have agreed to allow daughters, wives and kin to abandon the long cloak and face coverings.

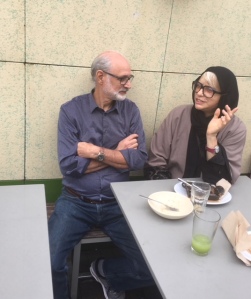

For me, when I was in abaya and with my husband, I thought “it’s good for him to think about the larger puddle ripple that goes on between men, women and the society they swim in “ because he’d never be thinking those thoughts if I weren’t wearing the garment. For me, at the restaurant: I imagined I stimulated the curiosity of people sitting at the tables next to us; maybe the couples will have a new conversation about their power relationship as it relates to the one they think my husband and I might have. Inside it all, my experience of Day 4 of the experience of being woman in an abaya with my husband generated a playful feeling and a lightness of spirit.

For me, when I was in abaya and with my husband, I thought “it’s good for him to think about the larger puddle ripple that goes on between men, women and the society they swim in “ because he’d never be thinking those thoughts if I weren’t wearing the garment. For me, at the restaurant: I imagined I stimulated the curiosity of people sitting at the tables next to us; maybe the couples will have a new conversation about their power relationship as it relates to the one they think my husband and I might have. Inside it all, my experience of Day 4 of the experience of being woman in an abaya with my husband generated a playful feeling and a lightness of spirit.

Leave a comment